Independence for whom?

March 23rd, 2019

I recently spent a day at Sea Ranch, a strange and beautiful place. Sea Ranch is a planned community with a distinctive architectural style: simple timber-frame structures clad in wooden siding, and gardens all planted with native flora. The Sea Ranch Design Committee enforces strict design rules on all 1,800 homes along that 10-mile stretch of the Northern California coast. The result is a cohesive, calming aesthetic unlike anywhere else I've been.

Depending on who you ask, Sea Ranch is either the beautiful manifestation of a bold vision, or it's an exclusive dominion controlled by rules put in place generations ago. My view: both interpretations are correct.

|  |

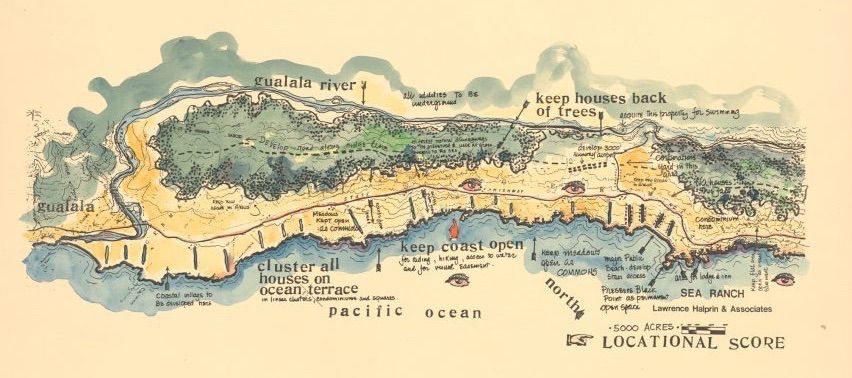

How did this eccentric place come to be? In the 1960s, a small group of architects bought the property, envisioning a community that harmonized with the environment. The guiding principle was to "live lightly on the land," inspired by the lifestyle of the native Pomo Indians. The architects created a strict master plan prescribing "clusters of unpainted wooden houses in large open meadow areas and not allowing fences or lawns." In the 50 years since, these guidelines have shaped Sea Ranch into something truly special, a sanctuary of natural beauty and subtle good taste.

This master plan is the key attraction, but it's also a major source of conflict. In 1972, California voters saw the private development as a threat to public coastal access, and, in direct response to Sea Ranch, they passed the Coastal Initiative to ensure public access to the state's beaches. With this regulatory change, the real estate developers who'd financed Sea Ranch wanted out.

This loss of control had a predictable result: The northern part was not developed according to the original plan. "Some folks say that there are essentially two Sea Ranches: the tasteful, quiet southern part and the suburban golf-playing northern sector," wrote Kenneth Caldwell in Archpaper. On one hand, this was a tragic collapse of an independent, bold vision. On the other hand, it was a victory for the freedom of the rest of the community to enjoy the coastline as they wished. Both interpretations are accurate, and both are important.

The plan for Sea Ranch is an example both of an individual's singular vision and also of collective conformity necessary to execute that vision. It reminds me of the dramatic storyline in The Fountainhead about Cortlandt, a housing project designed by protagonist Howard Roark. When Roark learns that his design was compromised, he heroically dynamites the buildings to prevent the subversion of his vision. One interpretation: a case for individual expression. Another interpretation: Roark imposed his wishes on others regardless of the impact on their lives. Again, I sympathize with both interpretations. The divergence from Roark's brilliant vision was tragic, as was the destruction of what was built.

The Objectivists I know usually assert the first interpretation, emphasizing the moral power of individual genius. In their rhetoric, they defend everyone's right to have the freedom to execute the kind of vision that Howard Roark represents. Unfortunately, this goal of universality is impossible to achieve—if everyone were a lone visionary, their plans will conflict, and there will be no one to support them in implementing those plans.

It's interesting that Ayn Rand chose to make her protagonist an architect, a profession whose work so deeply affects communities. The standard interpretation of The Fountainhead is as an allegory showing that freedom and self expression are a human birthright. But if Rand's sole intention was to glorify individual genius, why didn't she choose some other type of creative expression instead of architecture? When an architect designs a building, it affects the entire community. Many other forms of self-expression—sculpture, literature, or music—have effects that are far more contained. Why didn't she make Howard Roark a sculptor or a painter?

My reading is that this was a deliberate choice. I think that Rand understood very well that there is a tradeoff between the primacy of one man's vision and others' submission to that vision, and she was happy to bite that bullet.

What I takeaway from The Fountainhead is that Rand believed that some people are visionaries whose gifts the world should not suppress, and others are not worthy of that epic responsibility and should submit to the heroes' plans. I'm not sure if I agree, but I am quite sure that the universal individualism that most people ascribe to Ayn Rand's writing does not fit with the story she tells.

Sea Ranch's "enforced tastefulness" is even more invasive than the design of Rand's fictional housing project—an entire village of homeowners is submitting to the vision set by a few architects in 1965. The rules are rigid, prohibiting anyone's creativity but a small group of architects, long gone from the community.

Yet as I wandered along the pristine, rugged cliffs, winding between the stunning homes that are each unique and yet formed a coherent whole, I had a hard time not feeling gratitude that there was a brief window in time in which architects reined over Sea Ranch. The place is special, and it would not be what it is today without that strict control. The important question to ask is: Was that worth trading off the independence of everyone else? That question is one I still don't know how to answer.

Thanks to the friends who've been part of the journey with me through these ideas over the past few years. You know who you are. ♥

Notes

I must admit that I haven't read The Fountainhead since high school. It is quite possible that my memory of it is simply a Rorschach test that reveals what I've been thinking about recently more than it does about what Ayn Rand meant to tell the world. 🙂

To learn more about the history of Sea Ranch:

Finally, I usually try to balance the number of images with the actual amount of text in my essays, but the architectural style of Sea Ranch is so striking that I can't help but share more photos:

|    |

Keep in touch!