Google Maps Convinced Me to Ditch My Car

June 30th, 2016

I am always a little embarrassed when people find out that I had a car in college. I'm a transit geek after all, and I always encourage friends to take public and on-demand transit rather than generate congestion and consume parking spots. Despite all this, I drove multiple times each week last year, because I felt like it was my only real option to get to places I needed to go around the Bay Area.

Now, I rarely drive anymore, and I've become an avid user of public transit. Increasingly, my car has spent days and sometimes even weeks at a time in the same parking spot. What's the source of this change? You might conclude that my commute has changed or that my financial situation has shifted. Both of those are good guesses, but neither one is responsible for my embracing public transit.

No, in fact the source of the change is that Google Maps' transit layer is fantastic, something I discovered when I traveled to Berlin last summer. In the three weeks I was there, I relied entirely on public transit and, in turn, Google Maps to navigate the the German city's multi-model transportation system.

|

To be entirely honest, I was terrified of public transit before this point. I grew up in suburbia with minimal public transit options, so I had only used subways in my few childhood visits to New York City, during which my parents held my hand and guided our family through what at the time I perceived as a scary labyrinth filled with monsters quite a bit worse than the Minotaur. Combined with a handful of missed connections while attempting to traverse Chicago's bus network and what came to be an expectation of Caltrain's lateness, my experiences with public transit translated into concern and anxiety. Combine that with being in a city by myself where I spoke the native language at the level of a three-year-old, I was terrified that I would have no idea how to get around.

In other words, I simply did not know how to use public transit, because no one had ever taught me how to use it. But here I was in a city by myself, in which car-sharing services like Uber and Lyft were banned. So despite my concerns, with no affordable alternatives, I had to brave the transit system.

Armed only with my smartphone and boundless optimism, I stepped out of Berlin's Tegel Airport with a tiny ball of excitement in my belly. At last, I was going to prove to myself and to the world that my suburban upbringing hadn't cripped my spatial reasoning skills!

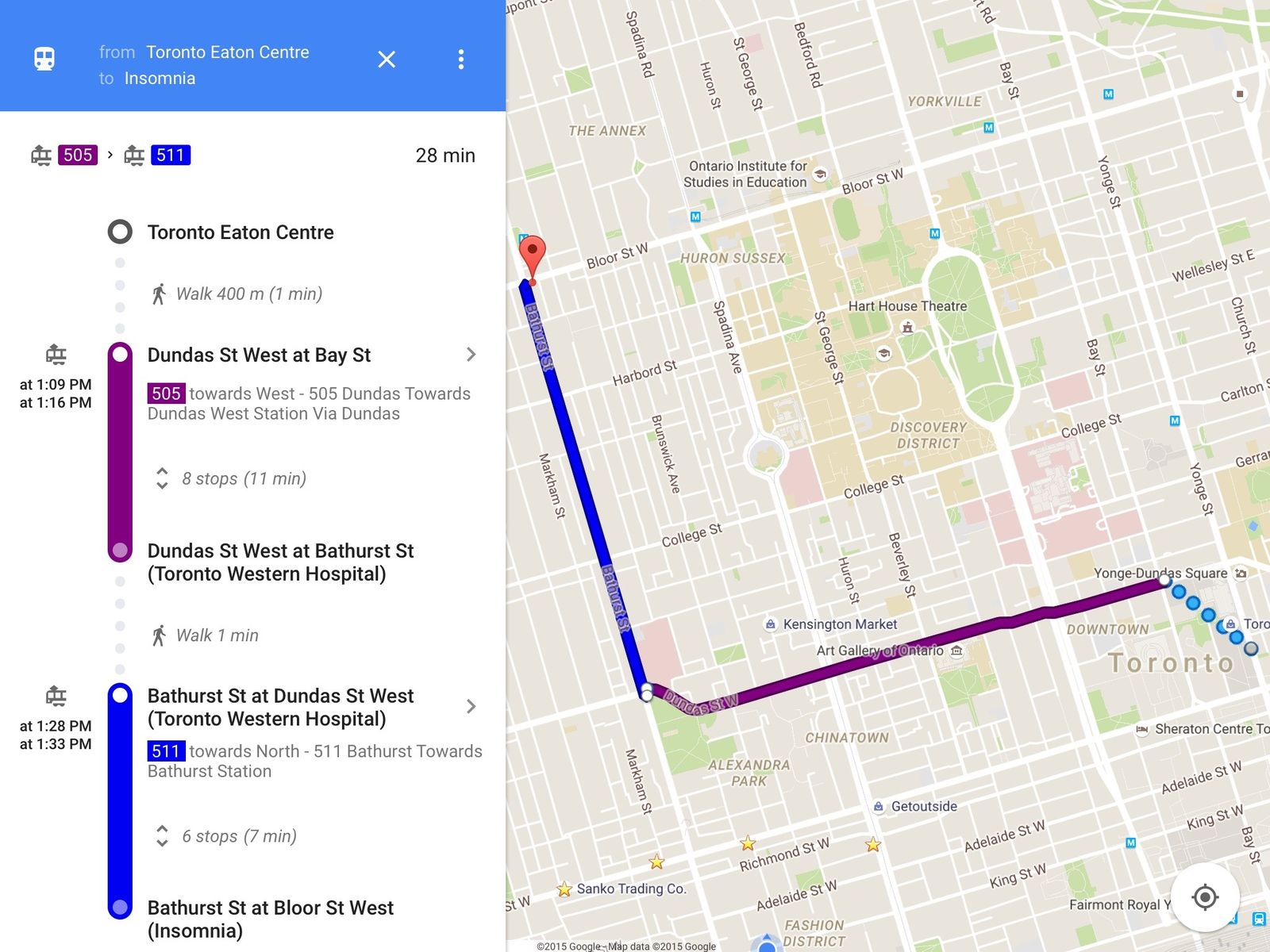

Imagine my disappointment (and relief) when I discovered that Google Maps can tell you step-by-step how to get anywhere with public transit as well as it can by foot or by car! Rather than fumbling around asking strangers for directions in my broken German or god forbid attempting to read the faded maps at the transit stations, I spent the remainder of my stay blissfully following Google's concise, accurate directions.

When I came back home to California, I figured "heck, if the directions were so great in Berlin then why shouldn't they work well here in the Bay Area, at the heart of the tech community and home to Google itself?" It was at this moment that the entire world of transit truly opened up to me. Stanford's free Marguerite bus system was no longer part of the background. It became a major fixture in my life, the way I get myself to the Caltrain, which I then use to get to Mountain View or up to the city. Before, the Marguerite was a mystery; now, the complexity is reduced down to a simple abstraction, a button tap away from instant knowledge of how to get from point A to point B.

I had some previous experience with the Caltrain, but it too became so much easier to use. It felt much more manageable, particularly for those multi-modal trips where I depended on connections with BART or the Marguerite or some other form of transit to get to my final destination.

In giving the Bay Area's various transit options another chance, I discovered a wide array of further benefits that I had not previously considered. I quickly saw "freedom from car ownership" as the real benefit rather than "freedom of car ownership". For one, I had much more time to myself to read, listen to podcasts, or catch up on emails and work. Rather than devoting hours of my week to mindlessly keeping my eyes on the road in order to drive between destinations, I am able to do whatever I want when I am in transit.

Furthermore, my greatest concerns were quickly squelched by experience. In particular, I was extremely worried about those trips where I didn't have access to public transit, off-the-grid trips away from arterial transit routes. This fear turned out to be basically unfounded. For one thing, despite popular gripes about how underserved transit is along the peninusla, Google Maps helped me discover that transit actually covers the vast majority of places where I want to go. Even in the South Bay, which I've always considered depressingly suburban, there is a thriving bus system that strings together the towns along El Camino.

In the few cases when transit truly does not serve the point in space-time to which I wish to go, on-demand services like Uber or Lyft are always an option, and they are surprisingly affordable for short journeys. The one use case for which I have not been able to find a suitable car-free option is weekend road trips, but even then there are always Zipcar rentals or borrowing a friend's car. In my particular case I also have the luxury of living close to my parents' home, which means I could also call upon them to borrow their car, and even in the most urban neighborhoods, most social circles have at least one person who would be willing to lend out their car for a special occasion.

My previously-held perception of public transit as unsafe and dirty quickly came to pass as well. While I still prefer to not take the BART late at night and I make a point of using the restrooms before boarding Caltrain (those toilets are truly nasty), at no point have I questioned my safety in my various public transit escapades along the peninsula.

The moral of the story here is that none of these systems are actually new. The Bay Area's transit system has been around longer than I have been alive, and the Marguerite shuttle system was in place and an option for the entirety of my Stanford career. Me entire behavioral shift can be attributed to that initial moment as I stepped off the airplane in Berlin and realized I had no idea how I was going to get from the airport to my hostess's home in Prenzlauer Berg. It took an initial shock to push me out of my default habits and reconsider my transit options.

There is a critical lesson to be learned here – cities can build the most state-of-the art transit systems and make them as accessible and convenient as possible, but unless individuals have a direct reason to reconsider their transportation decisions they likely will not make the shift.

This applies to a broad array of people beyond just me. We are at a particularly opportune time to change the way Americans – especially young people – think about mobility. Due to a broadening array of transit options and rising public interest in transportation due to the rise of on-demand transportation, people are open to reevaluating their transportation habits now more than at any other point since cars became a mainstay of American culture. A study by the American Public Transportation Association (APTA) found that people in the 18 to 34 age group are more likely than those of other generations to choose the most practical transportation mode for each trip, rather than the traditional decision to make cars the single mode of transit for all purposes. The rise of smartphones too has had a tremendous impact. The flexibility and control in linking modes of transportation brought by tools such as Google Maps improves the experience for everyone, not just for me when I was stranded in Berlin. Now, transit is open to anyone with a smartphone and not just savvy locals experienced with the complexities of multi-modal public transit. Combine these factors with the fact that the current generation is more aware than any previous generation of global warming, and the result is that young people are primed for behavior change.

Despite all of these factors, many Stanford students in my position continue to opt to have cars on campus and use them daily. Even as a strong believer in the need for people to shift over to more sustainable forms of transportation, it wasn't until a shock to my system that I truly reevaluated the necessity of driving day-to-day. I applaud Stanford and the Bay Area as a whole in their efforts to expand accessibility and convenience of the transit systems, but they should redirect some of those efforts to simply dislodging ingrained behaviors. Financial, personal, and social incentives are already quite well-aligned for many individuals to make the switch from personal cars to multi-modal public transit – they simply need that little nudge, encouragement to reconsider their choices and reweigh the pros and cons of their options. I predict that if drivers were to simply reconsideer their options, many would change their behaviors without any other change to the system, just as I did.

Keep in touch!