Field notes: Panamá, SEZs, & biotech

February 5th, 2022

I just spent a week in Panamá City, and figured I'd share my observations in case they're useful to anyone else interested in similar questions.

The purpose of the trip was to research locations for a gene therapy/stem cell clinic that my friend is planning to start. I also explored a few of Panamá's Special Economic Zones (SEZs) as part of my ongoing research about startup cities, as well as to learn about the opportunities they offer for businesses like my friend's clinic.

The fact that this was a goal-oriented trip actually made it even more fun. I recommend this as a way to organize your travels. For me, travel is most satisfying when I have a concrete goal—in this case, "where's the best place to open a gene therapy clinic in Central America?"—because it forces you to actually learn about the place rather than take whatever path just happens to be pre-paved for tourists. You bump up against real constraints in the real world, rather than interacting with some manicured narrative of what the place is about. Best yet, you learn about what its future might be, not just the past.

Another reason I was excited to visit Panamá was that I lived in a tiny rural village called El Águila in 2010 as part of a high school exchange program. I hadn't been back in 12 years, so I was excited to reconnect with my host family. It was fascinating and invigorating to see how the country had changed!

But I'm getting ahead of myself. I've broken down my field notes into three sections:

- Stem cells, biotech, & regulation

- SEZs & new city developments

- Panamanian urbanism, economic development, & general observations

I. Stem cells, biotech, & regulation

We learned some conflicting information about the legal status of commercial stem cell treatments in Panamá, and I'm still trying to sort it out. If you know a doctor or lawyer who specializes in this area, I'd love to hear from you.

Before the trip, I did some online sleuthing to get some background on the issue. Highlights:

- Panama passed a law in 2004 making embryonic stem cell work illegal, which at the same time opened the door to legally working with adult stem cells in ways not yet approved in the US.

- Dr. Riordan at the Panama Stem Cell Institute has performed "over 10,000 procedures" using stem cells to treat autism and many other conditions since they opened in Panamá in 2006. (Parents' Guide to Cord Blood)

- They sell commercial stem cell treatments (e.g. they charge $13,000-$18,000 for autism treatments) so they're not just doing clinical trials, which you're not supposed to charge for.

- The article says that the clinic and lab are "fully licensed by the national medical authorities and adhere to international standards".

- The clinic registered a clinical trial for autism in 2014, which included 20 participants.

- The clinic was originally based in Costa Rica, but it moved to Panamá in 2006. (Stem Cell Transplant Institute)

- It appears that they moved because they were not allowed to perform treatments because "efficacy and safety were uncertain", although they were "allowed to store adult stem cells extracted from patients’ own fat tissue, bone marrow and donated umbilical cords".

- Stem cell treatments have since been approved by Costa Rica's government, and there are active clinics that offer these treatments to patients.

- BioXcellerator writes that "not only is stem cell therapy legal in Panama, it is quickly becoming one of the global leaders in research of non-surgical therapeutic options for care."

My general understanding from that pre-travel prep was that commercialization of stem cells is legal in Panamá, and that it's a small but growing industry. However, when I got boots on the ground, I began to hear different things...

- Firstly, there are very few stem cell clinics here. From talking to several medical professionals, I was only able to learn about two in the entire country: Stem Cell Institute and Cordon de Vida. This was surprising to me, since some uses of stem cells have been legal in the country since 2004 (as described above) and I'd expect droves of doctors to take advantage of the opportunity to serve medical tourists who can't get these treatments in the US.

- I met with a Panamanian orthopedic surgeon who's considering starting a stem cell clinic for medical tourism. He didn't seem terribly concerned about the legal status, though he hadn't opened the clinic yet so he may not be aware of the hurdles.

I met with "the only stem cell researcher in Panamá" to understand her perspective on the technology's legal status.

- She's opposed to commercialization of stem cells in Panamá for anything that (a) doesn't have lots of clinical trials first and (b) hasn't already gone through approvals through the Panamanian FDA.

- She considers it illegal to sell stem cell treatments in Panamá, since they don't meet either of those criteria.

- However, it's not really enforced so there are several commercial stem cell clinics that have popped up charging for "clinical trials", which you're not supposed to do

- She's extremely excited about the future of stem cells, but just thinks it's too early to be offering them in a commercial setting. She believes that the technology is still at the stage where it's only ethical to use it in clinical trials, in which the patients do not pay for the treatment.

- She hopes that Panamá becomes a center for medical tourism because it is on the cutting edge but not because it's a haven for people escaping the US FDA.

Misc/related thoughts:

- I've heard there is a shortage of medical professionals in Panamá, which could be a barrier to becoming a medical tourism hub. Additionally, Panamanian labor law states that "only 10% of your business workforce can be filled by foreign workers", which means the shortage can't be solved by simply importing talent from elsewhere.

- Stem cell treatments are legal in Costa Rica and Colombia, so I'm planning a trip to those countries as well to dig into similar questions. If you know anyone I should speak to while I'm there, please let me know. I'm also open to other suggestions for places that welcome stem cell treatments.

My overall takeaway was that you could probably start a commercial clinic and possibly operate without problems for years, but you may get shut down or fined at some point in the future by the government. If anyone knows more details about this or can correct me, please reach out!

II. Special Economic Zones & new city developments

I visited three of Panamá's SEZs. I also met with a lawyer who specializes in Panamanian SEZs, which gave me a very helpful bird's eye view of how the legal frameworks that support the SEZs work.

Each SEZ in Panamá is different, but the general similarity is that they all provide benefits to their tenants such as:

- higher quality infrastructure than what's typically found outside of the zone

- a cluster of talent that is concentrated in a single focal point

- special pre-built facilities (e.g. laboratories or warehouses)

- tax exemptions on tariffs, remittances, VAT, local direct taxes on capital, corporate income tax

- special immigration and labor incentives (e.g. ability to expedite visas)

I visited three SEZs: Ciudad del Saber, Panamá Pacífico, and Porta Norte.

- business model: non-profit foundation whose revenue comes from renting out facilities to businesses/institutions

- it's been self-sufficient for many years now, though it started with a land grant from the government in 1998; took a credit line with a local bank for first 10 years + the EU gave matching funds → CDS paid all of this off by year 7

- 120 hectares / 300 acres, 200 buildings (mostly built for the former Clayton US military base and now adapted to new uses)

- the idea was to "exchange soldiers for professors, bullets for books"

- rents out some housing (~100 houses I think), but it's not a central focus

- focus on housing research, innovation, and NGOs

- businesses need to apply, meet a bunch of criteria, and get approved by CDS' board of directors

- tenants in CDS needs to support "innovation" in some way — they won't accept purely commercial operations, but they'll accept businesses that have a research component

- the board only meets 4x per year, so it takes some time to get established in CDS

- organizations based in CDS include:

- stem cell manufacturer MediStem

- the Red Cross

- University of South Florida has a medical research lab

- e.g. Dell wanted to put a call center at CDS, but CDS said "no" because it didn't have an innovation component and they established elsewhere

- CDS is considering hiring a liaison to help medtech companies within the zone to interact with Panamá's Ministry of Health, though that role doesn't yet exist

Bird's eye view of part of Ciudad del Saber

Food court area within Ciudad de Saber

- feels like it's built to enable Panamá's catch up growth (which is a great goal!) but is not cutting edge as far as urban design or innovation (which is what I'm personally more interested in)

- warehouses; to my untrained eye, it seems world class as far as enabling logistics

- modern office spaces, very corporate

- there's a residential area that is similar to a typical American suburb

- multiple Panamanians I spoke with gushed about how beautiful it was; seems to be a very aspirational place to live

- 1,400 hectares / 3,450 acres – it's HUGE!

- the land was formerly used for the Howard US Air Force Base; some of the buildings have been left intact, but most have been replaced

- established in 2004, with a 40-year master plan to develop it over time

Scale model of Panamá Pacífico

The International Business Park section of Panamá Pacífico

Project #3 – Porta Norte

- the vision is to be a walkable traditionally-planned neighborhood but with modern amenities

- currently being built; does not yet have SEZ status

- university will be an anchor tenant

- 260 hectares / 640 acres

- it's on the city outskirts right now (~25 minutes from the city center by car), but the demographics of Panamá make a perfect pyramid + they're going to have a metro stop in a few years, so I expect it'll be a very attractive place for growing Panamanian families to move in the coming years.

- I'm very excited to return in 5-10 years to see what it's become!

Rendering of what one of the streets in Porta Norte will look like, with emphasis on its pedestrian- and bike-friendliness which is so rare in Panamá

Henry, the founder of Porta Norte, gave us a tour of the construction site

There are several different SEZ regimes in Panamá. To me they were an odd patchwork rather than something designed with an overarching vision in mind, though I suppose that's true of most things. Each of them has a complex set of constraints and rights that overlap with each other in unintuitive ways. This is my rough understanding of how they fit together, though please note that there is a lot more complexity to exactly how they work:

- A 1948 law created the Colón Free Zone. It provides tax incentives to entrepreneurs, and it was the first Free Trade Zone in the western hemisphere. I've heard it's falling apart and no longer considered cutting edge, but it was trailblazing in its time.

- A 1998 law created Ciudad del Saber which endowed a non-profit foundation with land. The non-profit rents facilities to "innovative" businesses, research institutions, and NGOs and is required to reinvest any profits back into the infrastructure of the zone.

- A 2004 law created Panamá Pacífico, which gave a private developer the right to buy up large swathes of land at a fixed price over the course of 40 years as it develops a warehouse area, a business park, and a residential area.

- A 2011 law allowed developers to apply to make their property a Free Trade Zone, regardless of where it is in the country. Before this law, if you wanted to start an FTZ, you had to get special legislation passed to get that status (e.g. the laws that enabled Colón and Panamá Pacífico). Now, it's just an application process (albeit a long and somewhat nondeterministic one, to my understanding).

- The land for the proposed FTZ must be at least 2 hectares, and it must be enclosed.

- There are now 20 FTZs in Panamá.

- This is the type of FTZ that Porta Norte is applying to become.

High level takeaways:

- Panamá has a unique situation that it has large swathes of land near the city. That land had previously been dozens of American military bases from when the US owned Panamá Canal. This gave the Panamanian government prime real estate to use for the development of SEZs. By contrast, most developments of that scale have to happen in farther off parts of a country, because the land closest to population centers has generally been consumed already.

- Having "innovation zones" that are specially decreed by the government to have special privileges seems to make them inflexible in what they're able to do, and as a result they end up being "overfit" to the needs of that time and in turn become obsolete quickly.

- The ongoing decay of Colón Free Zone seems to be an example of this. From afar, it seems to be an issue of being bound by rules that weren't flexible enough to adjust with the times.

- Although they both appear to be thriving, Panamá Pacifico and City of Knowledge gave me a sense of sterility and over-prescribed order that makes me worry that they may be inflexible in the future as the world changes around them.

Side note – The Open Zone Map is a useful resource for learning more about SEZs worldwide.

III. Panamanian urbanism, economic development, & general observations

Economic development: Panamá has achieved tremendous economic development since I was here as an exchange student 12 years ago. I got to see it up close and personal, because I reconnected with my host brother, Sami, and he has transformed his life since I saw him last. Seeing the progress they've made was one of the happiest experiences I've ever had.

- El Águila (the rural village where I lived in 2010) didn't have a paved road when I lived there. Since then, they've built a road that connects it to the rest of the country. While it used to take 4 hours to get to Panamá City from El Águila, it now takes 2-2.5 hours.

- When I lived there, El Águila didn't have running water, glass for windows, or electricity. Now they have all of those things.

- My host brother is now a lab technician at a biology research institute. He started out as a construction worker when he moved to Panamá City, but he loved biology, so he decided to do extra training on the side to learn how to work in a lab. He now works at Panamá's premier tropical diseases institute, Instituto Gorgas.

- Between 2010 and 2019, Panamanians' income more than doubled, as measured by PPP (Purchasing Power Parity).

- In 2010, Panamá's PPP was almost $15,000.

- In 2019, Panamá's PPP was almost $33,000.

- In 2020, Panamá's PPP sadly plummeted to $27,000 (I assume due to the pandemic), but hopefully they'll bounce back when the 2021 numbers come in.

- One of my Panamanian friends recently went to the passport office, which gives people in line a different colored slip depending on whether they are renewing their passport vs getting a passport for the first time. When he looked around, almost everyone there was getting their passport for the first time. He saw this as a great sign that more and more Panamanians are getting rich enough to travel abroad for the first time.

Me & Sami, my host brother

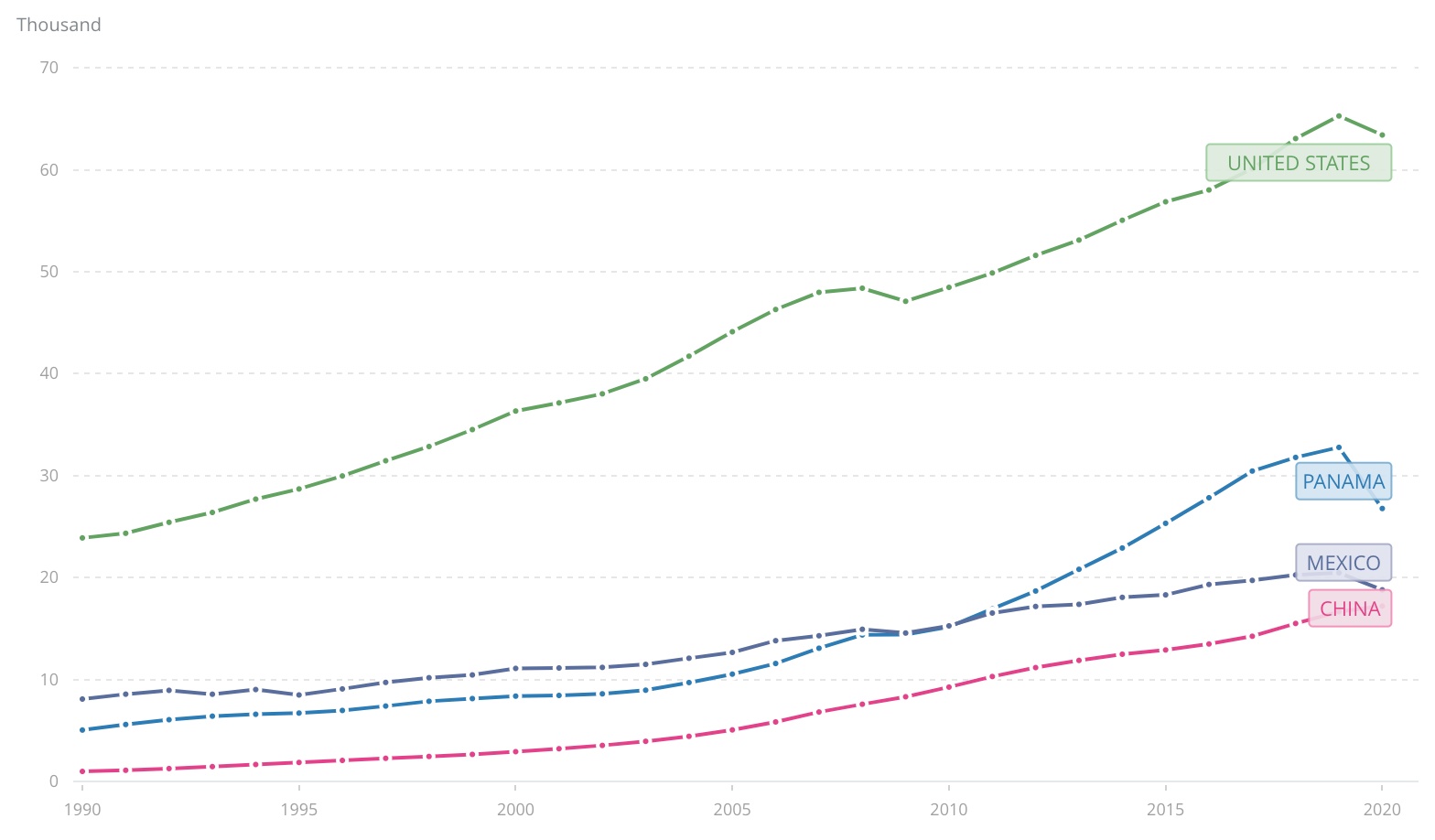

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) of Panamá, USA, Mexico, China

Urban form

- By and large, Panamá City is uncomfortable to walk around, but there is some really beautiful old colonial architecture. Also if you're into Miami-style modern high-rises, you'll definitely find something pretty comfortable.

- Casco Viejo is a beautiful old town. It's similar to Old San Juan in Puerto Rico if you're familiar with it, though at night it feels more unsafe and it's smaller and thus closer to slums.

- La Cinta Costera, the park that runs along the waterfront, is really lovely. Walking along the coastline at dusk is one of my favorite memories of Panamá City.

- It reminded me of South Pointe Park in Miami Beach, except with Brickell as a backdrop rather than South Beach's art deco buildings.

- There's a lively outdoor food court area that reminded me of Singapore's hawker stalls. It's right on the marina, so you can savor your ceviche while watching the fishermen haul in the corvina its made out of.

- Unfortunately I didn't enjoy the other parts of the city that I saw as much. I saw two types of neighborhoods primarily: (1) soulless high rises with huge setbacks, lacking trees (especially for what's needed in a place where the sun is so intense!), and separated by a sea of parking and traffic and (2) cramped, low-grade buildings packed in with informal slum housing made of tin and scraps.

- Comparisons to other cities you might be familiar with...

- Panamá City reminded me a lot of Singapore, except it's not as clean or safe and generally not as well done. Singapore's urbanism isn't really my style, but I see what it's going for, and Panamá is aiming for something similar.

- The Latin American city I'm most familiar with Buenos Aires, and so I find it a useful comparison point. Buenos Aires certainly has serious problems too, but its nice areas a much larger than Panamá City's nice areas. It's surprising if you just look at the PPP for each country, since Panamá's PPP is 50% higher than Argentina's. It's a good reminder that wealth as measured by PPP is not perfectly correlated with all good things (though it's certainly correlated with a lot of good things!).

- Even in the modern high rises, there were lots of haphazard details, e.g. I tripped over a step into a bathroom in fancy lawyer's that clearly didn't followed any building standards that would be typical in USA. This might be chalked up to my clumsiness though. 😉 There were also lots of surprisingly narrow hallways in miscellaneous places, which would definitely not be up to American fire codes but may be up to code here.

|  |

Casco Viejo, the old part of Panamá City, is a beautiful neighborhood. Some of the buildings are abandoned however and have squatters, so you need to be careful when walking there at night. | |

|  |

La Cinta Costera, the waterfront park, was one of my favorite spots in Panamá City. | |

|  |

Unfortunately I didn't find any other neighborhoods I really liked. It was generally very car-oriented and barren of trees, which are so so so important when you're walking in 90℉ / 32℃ heat with 90% humidity. | |

|  |

Panamanians are building a ton!

- They're building the Panamá City Metro and making great progress.

- The first line of the Metro was built in 3 years between 2011-2014, and the first phase of the second line was completed in 4 years.

- By contrast, it took NYC 10 years to build just 3 stations for the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway. (And that was just the construction! The original proposal was made 100 years ago, and an initial attempt at construction began in the 1970s.)

- In the region around Porta Norte, there are tons of other developments occurring at the same time. Those seemed to be more traditional suburban communities, but still exciting to see the country build so much and develop.

Panamanians have a very global, outward-looking culture:

- There is much more Asian influence in Panamá than I expected. I saw a lot of Chinese immigrants when I was here 12 years ago, but they didn't seem very assimilated, at least not in the countryside where I was living. In Panamá City today, most high end restaurants you go to are some sort of Panamanian-Asian fusion. Both Sami (my host brother) and Henry (the founder of Porta Norte) said that they eat Chinese style foods often. My trip also happened to coincide with Chinese New Year, and there was a huge celebration that took over the entire neighborhood where I was staying.

- From the people I spoke with (which admittedly is not an unbiased sample, though I did speak with people from all sorts of professions and income levels), they are all very positive towards global trade.

- Panamá was effectively a US colony for many years, so I thought perhaps there would be negativity against Americans, but the people I spoke with generally love America and want closer ties with it both economically and culturally.

Fun facts

- I learned that Zonians refers people associated with the Panama Canal Zone. The Zone was a political entity which existed between 1903 and the absorption of the Canal Zone into the Republic of Panama between 1979 and 1999. People born in the Zone received both Panamanian and American citizenship. John McCain is probably the most notable Zonian.

- Two routes were under consideration for the Panama Canal: Nicaragua & Panamá. A major selling point in favor of Panama was the flat arch of Santo Domingo Church. The centuries old arch is so structurally unsound that the builders knew Panama couldn't possibly have earthquakes.

As always, if you know something you think I might not know, give me a holler! I'm eager to learn more about Latin America, SEZs, biotech regulation, and the intersection of all three.

I hope these notes were helpful, or at least interesting, to you. If you ever need a consultant to investigate the legal or economic situation in another country like what I did in Panamá, let me know. I might be able to help.

Keep in touch!